The Devil’s Mathematician

Min-Hee swiveled her right hand slightly and the holographic human hippocampus rotated in midair. “As you can see, our model proposes two new neursembles that seem to better match the canonical results from Steinberg et. al. Traffic output at the hippocampal CA1 subdivision more closely agrees with real-world I4h nanite feedback than those models which utilize the standard Holtzmann-Kuznetsov operators. For this reason, I believe the mathematical framework of our adjusted tav operators better models the observed output.”

Min-Hee slowly splayed her fingers outwards as the view zoomed in to the CA1 pyramidal neurons that connected to layer V in the entorhinal cortex. Artificially labeled were neural loci suspected of synchronizing local ephaptic resonance. She tapped her left forefinger and the standard dynamical graph theory connectomic representations of the Miyazaki scaffold began to overlay in green.

She allowed the attendees to consider the conundrum they already knew well unfold in midair: How did the seemingly ethereal “mind” emerge from the tissues of the brain? More specifically, how did dynamic neuronal populations contribute to the maintenance and alteration of neuralets, neursemblies, and neursembles, … the “virtual” containers for words, images, thoughts, and ideas?

The questions were at the heart of the ancient mind-body problem that had been debated since antiquity. Did the mind arise due to magic? … the soul? … or because of nonlinear dynamics? The brain was basically an intricately structured bag of water. How did a bag made up of 73% water and roughly eighty-six billion neurons produce art, music, language, and mathematics?

During the preceding century, tens of thousands of neuroscientists, neural engineers, A.I. researchers, neurobalanists, connectomists, and Gods from Mount Olympus had tried to answer that question without success. Holtzmann had come closer than any of them, … but had still not hit the bullseye. … Not that the world seemed to care that much. His innovative work had led to emergent, neuromorphic, learning algorithms that ran everything from the holo displays on cereal boxes to nanofabricators, and in many cases were even quantum-aided. Why recreate the human brain virtually when emergent pattern matching could imitate much of consciousness? Algorithms that could be applied to almost every facet of life that did not require true creativity, imagination, or intentionality.

Min-Hee looked out at the small room where twenty real and virtual people sat. Brave souls every one to risk possible somnolence at an unknown grad student talk. She could have given the talk through sensorium but this was her first real paper, and she felt an odd antiquated desire to be personally present. “We believe that by adjusting the Holtzmann operators and using a regression term, our model better fits the Steinberg data.”

This year, the American Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the IEEE, had decided to hold their Joint Neural Engineering Conference in downtown San Francisco at the rebuilt Moscone Centers. What had begun as a small informal gathering of like-minded scientists fifty years earlier had grown into one of the larger academic conferences in the world. The current format now showcased thousands of talks spread throughout the convention center over the course of ten days.

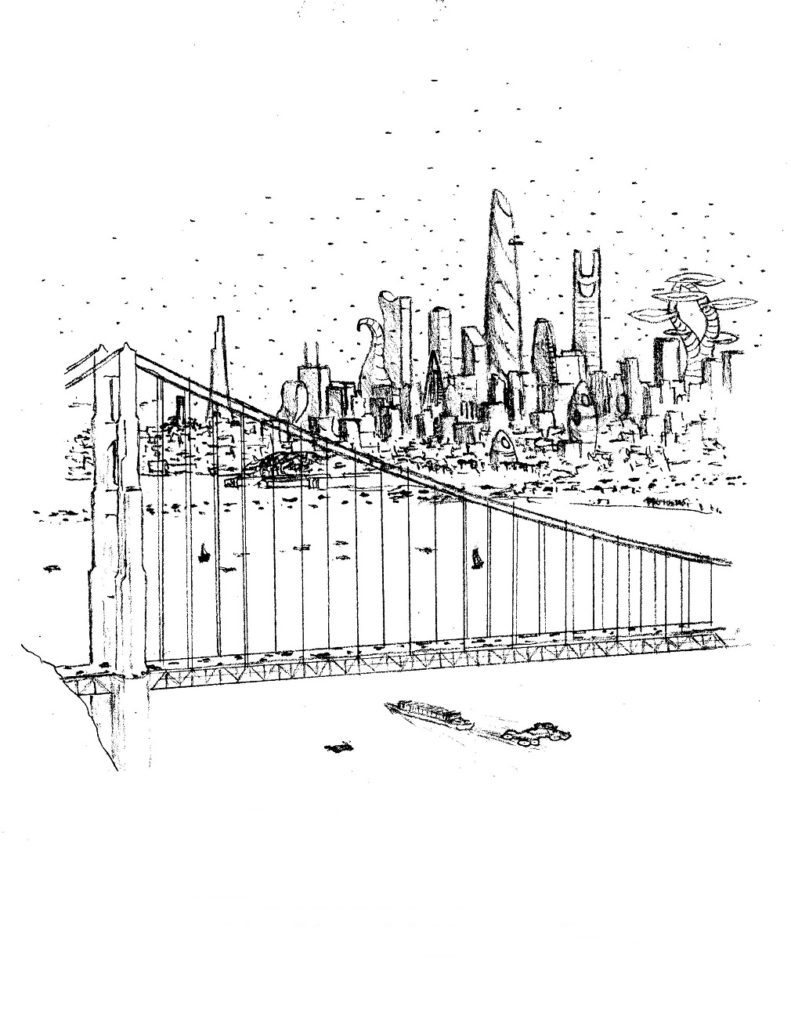

Min-Hee had visited San Francisco several times in sensorium but never in the flesh. She had arrived three days early both to prepare in her hotel room and to catch some of the major tourist sites. On her first morning out she had used the revamped and expanded trolley system near Market Street on the Powell/Hyde line and ended up adjacent to the Fisherman’s Wharf area. From there, she had strolled back up to Bay Street and past the floating farms to the world-renowned mathematics maze within the former Fort Mason. She paid the entrance fee and set the difficulty to “professional,” the highest level but also took advantage of the avatar guide. On the twenty-sixth puzzle, she answered a question about hyperbolic knots incorrectly and the maze closed in and “killed” her as she laughed. She then meandered down to the Marina district where she caught her first wonderful glimpses of the Golden Gate. She gawked at the homes along Marina Boulevard as octocars streamed by overhead and continued on to Crissy Field and eventually up to the Golden Gate Bridge Welcome Center.

At various points, her optioimplants pointed out the still extant damage from the quake of forty-nine that had brought the city to a standstill. Surprisingly, only 2361 people had lost their lives in that 7.8 magnitude wave of seismic destruction, which had resulted in 587 billion dollars in damage. The quake had been twenty-nine orders of magnitude less than a magnestar flare but more than sufficient to upend the center of global innovation. Approximately 107 thousand buildings had been damaged along with 273 thousand people displaced. Most of the major structures, …. the Golden Gate Bridge, the San Francisco – Oakland Bay Bridge, the Transamerica Pyramid, the Coit Tower, City Hall, and the numerous skyscrapers of the financial district had been spared, but countless others had not. She looked out slightly to her right and gazed at all that had been constructed since the Second Fall, … the Imex 2k, the Biomes, the growing GenAR arcology spires, the award-winning Dragon’s Tail, and the outstretched World Tree. The Bay Area, which now held seven million people had surpassed Austin as America’s seventh-largest metro area. The Bay had not only recovered, … but come back with a dragon’s fiery blast.

The Bay’s initial misfortune had also led to a major funding increase for geophysics. Large-scale, quantum-aided, A.I. simulations of the Earth’s outer crust, its lithosphere, now routinely tried to forecast the chaos and self-organized criticality that underlay the slow creep of tectonic plates. Japan, China, the United States, Peru, Iran, Greece, and Indonesia had all dedicated Level I Gods to models that better predicted the movement of tectonic plates using reworked adaptive mesh refinement. The Japanese Geological Society had even tasked their Gods with the simulation of von Neumann self-replicating nanites scaled massively upwards to release tectonic stress at critical fault junctions rather than waiting for it to accumulate into major earthquakes. Min-Hee knew the primary technical hurdle of these plans was manufacturing nanites that could withstand the incredible temperatures and pressures common to the lower crust and mantle. Whether the research would actually benefit the Bay Area in time for the next large seismic release remained an iffy proposition.

Min-Hee bypassed the Welcome Center with its large, friendly, floating, holo signs and headed straight up the path to the Golden Gate itself. A crisp wind was blowing as she mingled with hundreds of other tourists to walk out a few hundred meters along the bridge and gaze. She had looked down at the restored Fort Mason and back slightly southeast at the skyline of downtown. In front of her a kilometer out, a steady stream of aircars crossed in both directions between downtown and Marin County.

To her left, she caught sight of the construction cranes in Sausalito and had to suppress a smile. A service academy for the United States Space Force was finally being built for the twenty-seven-thousand-member branch. Min-Hee could easily see the site transitioning into a future “starfleet academy” at some point.

Slowly, she turned around and looked out on the Pacific Ocean toward her home roughly nine thousand kilometers away. Like all tourists, her optioimplants recorded her voyage for later and caught some of the fog just now hitting the headlands of southern Marin County. For half an hour, she had watched as the late afternoon sun set over the Pacific.

God, just to be here on the Golden Gate when my ancestors only a few short generations ago had lived out all of their lives in North Cholla Province.

Without even being aware of the change, Min-Hee’s mind had switched to the various differential equations which modeled the strength and forces on the bridge. The estimated nine hundred and ten thousand people that could stand packed on top of one another before the main support cables would begin to fail and the magnitude 8.3 Richter vibrations the supports could handle. She suspected that if the bridge ever did fail, it would quickly be rebuilt not because of its traffic facilitation but due to the unique iconography it represented in the minds of the entire Bay Area.

Without a specific plan, Min-Hee had wandered back down to the Welcome Center and watched the holographic displays show the time-lapsed replay of the effects of that fateful day on the Golden Gate Bridge. As always, she was left in wonderment that the Universe followed mathematical relations that if understood correctly, allowed people’s lives to be saved or improved.

From the Welcome Center, Min-Hee had strolled into the Presidio, and the busy and elegant towers of the re-established United Nations, and then down to the solemn San Francisco National Cemetery. Row after row of white tombstones stood in the light breeze and pristine silence commemorating the thousands buried there. As she walked by some of the headstones, necrotars shimmied into existence and inquired about her. A young enlisted sailor who had died fighting pirates in the Straight of Hormuz asked if she would be his pin-up girl. Several rows further up, she ran into the shimmering, hologram necrotar of a retired lieutenant commander who explained the conundrums of the Vietnam War to her.

As Min-Hee listened to him, she had reflected on the unique culture and viewpoints that Americans held. Colonies of poor farmers trying to free themselves from mismanaged crown oversight in the eighteenth century had eventually led the world to victory in World War II and the colonization of Mars. Their ability to save everyone from tyranny and yet be their own worst enemy. The horrible conflicts that had pulled at America’s most cherished ideals, from the Civil War to the McCarthy Trials to the Insurrection Attempt to the Debt Riots and Instability Clashes. That unique American addition of proper checks and balances had saved them again and again in a world that changed faster than ever before.

After her discussion with the commander and without realizing it, Min-Hee had walked all the way back to Fisherman’s Wharf and the tourist shops that lined Jefferson Street. When her feet had begun to ache, she found herself eating surprisingly good crab cakes and shrimp at inflated tourist prices.

Some papers rustled and Min-Hee raised her head to catch sight of the man sitting three rows back who had begun scowling at her almost from the beginning of her presentation and continued to do so now. He was partially blocked by another attendee and her optioimplants had not registered him. He appeared to be roughly fifty-five years old, tall and thin with receding black hair, a long aquiline nose, and a jostle of sharp angles for a face. He adjusted his old-fashioned eyeglasses.

He caught her eye. “You’re wrong,” he said clearly and confidently.

“I’m sorry, … do you notice an error?”

He stood up and scratched his thinning black hair. “Your ‘tav operator’ is a slight rehash of Berlman’s work from, … what, …. three years ago? If it was wrong then, … why would it be correct now? And what is this regression stuff? …. Nonsense.”

One of the attendees sitting in the front row caught sight of the man and whispered, “That’s Avenivich!”

Min-Hee instantly knew the name and adjusted her gaze so that her optioimplants could bring up the AllThing profile of the man. Gregori Avenivich was a Russian mathematician and one of only three people to ever win a Fields Medal for neural network research. A prize regarded as the Nobel Prize of mathematics until the Nobel Committees had decided several decades before to present awards in five new areas; biology, engineering, social and behavioral sciences, climate science, and finally, … mathematics.

Her implants began relaying a spool of information down the right side of her vision, but for the most part, it simply reaffirmed what she already knew. Avenivich had grown up in a wealthy family of merchants living in the suburbs of St. Petersburg and had been a wunderkind. He had begun to multiply at age three and had learned calculus from tutors starting at eight. At twenty, he had been awarded his doctorate from MIT in analytic number theory.

From there he had branched to algebraic topology and graph theory, and eventually to the thorny issue of neural networks. He had immediately attracted attention for his ability to interweave several disparate areas of mathematics to resolve networking and connectivity problems that had stymied countless others before him. Topology, partial differential equations, algebraic geometry, differential geometry, probability theory, … no area escaped his attention for a thorny problem that angered him.

Those advances had led him to worldwide commendation and praise. Rapid tenure at MIT at twenty-four and fourteen major mathematical prizes. After a decade at MIT and two at Harvard, he had decided to head to warmer weather with an endowed chair at Stanford less than sixty kilometers from the Moscone Center.

But Avenivich had attracted even greater attention for his rapid math confrontations across the AllThing and sensorium. Contests that pitted two or more mathematicians against each other to solve a problem within a given time limit. Much like his interests in tennis and chess, Avenivich relished the opportunity to face off against other gifted mathematicians in the pursuit of large cash prizes.

He had also employed this predatory style during numerous academic talks. Almost nothing was further removed from confrontation than a scholarly mathematical or engineering presentation. Even the greatest revelations and most surprising research results were staid affairs where the only real risk was an uninterested bystander snoring. The most inspiring presentations rarely generated more than a few raised hands with everyone then quickly filing out to the far more enticing refreshments table.

And yet Avenivich had a habit of turning any talk he attended into a heated Mytilenean debate. He interrupted speakers in mid-sentence and uttered harsh groans with results he particularly disagreed. He followed up with caustic comments at the end of talks and frequently came to the holo board to give wider life to a speaker’s incompetence. He seemed to derive glee from demolishing those less capable or gifted. Over the course of 358 rapid-math contests and/or academic talks, only five individuals had ever broken even with him, including famously, a then-older Tao. None had ever defeated him directly at the holo board, and his 353-5-0 record had not only earned him sixty-seven million dollars in prize money but an opportunity to parrot it at every occasion that presented.

A man much like Avenivich more than two centuries before had been Niccolo Paganini, considered by some to have been the greatest violinist who ever lived. A talent so phenomenal that he could play three octaves across four strings in one hand span. A man so gifted with the instrument that it was rumored he had sold his soul to the Devil for the ability to play in the manner he did. Gradually as time passed in some quarters, his unofficial sobriquet had become “The Devil’s Violinist.” Like Paganini, whom Avenivich resembled both physically and in temperament, jokes had circulated for years that he had sold his soul to the Devil to obtain his mathematical talents and the minacious manner in which he often employed them. And so was born the “The Devil’s Mathematician.”

Why in the hell Satan had decided to send his mathematical toady up the peninsula to attend Min-Hee’s talk in the flesh remained a mystery. Min-Hee was a nobody in the academic hierarchy, … a second-year doctoral student still wet behind the ears. Asmodeus alone knew why he would send his top henchman to embarrass a bottom-feeding grad student.

“The regression term is something I added to modify the Holtzmann Operators because the resulting tracting modeled the CA1 subdivision slightly better, and I think that they … “

“I applaud you for your creativity. They have an air of the transfinite about them but are still wrong. Simply not needed, and while Berlman’s model appears to align with the most recent nanite tracting results on the surface, it is wrong as well.” Avenivich then used his right index finger to trace out an equation on the holo board floating in mid-air. “You know this connectomic relation?”

Min-Hee had studied some of his theorems and postulates but was not familiar with the exact equation he had written out. “I’m sorry, it seems so familiar. I have studied your work before Dr. Avenivich, and I …”

“Evidently not enough because this equation sets up the probable interplay between thought space, tract entropy, and Shannon-Hartley.”

“I still believe though that …”

His minacious gaze met her eyes, “And you believe wrong. Please stop giving talks on subjects you know nothing about and head back to whatever institution allowed you into their graduate program. Put in the time to master the basics before trying to expand on them, … to say nothing of lecturing others.”

Min-Hee, rarely given to sentimental emotion, felt an unwelcome visitor at her eyes. Tears threatened and there was something about The Devil’s Mathematician that seemed to be awaiting just that result.

She was about to turn her head to the side to pretend to get a better look at the holo board as she waited for the tears to abate when she changed her mind and decided to look directly at him. She knew some dick in the room would be recording, and she didn’t want to appear on the AllThing as one of Avenivich’s victims, but at just this moment she didn’t give a damn.

“Why are you doing this? I am nothing to you,” she said as a single tear betrayed her and tracked slowly down her right cheek.

“Only draft on someone else’s innovation if you have something truly worthwhile to offer. You’re going to have to get a hell of a lot better in this field if you wish to swim with the whales.”